In terms the story of its past use, the Schuylkill River is still a hidden river. And while we know more and more about our emerging built environment we know less and less about the historical/cultural forces [attitudes toward land, attitudes toward users of built space, attitudes toward public and private rights] that wrought so much havoc on this section of our urban environment.

For most of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the east bank of the Schuylkill between the present-day Vine St. Bridge to the defunct Callowhill St. or Spring Garden St. Bridge was what could be called a “waste district” or a microeconomy revolving around the production, storage, and reuse of municipal waste. A 1922 map of the area (below) shows a powerhouse of the Hestonville, Mantua and Fairmount Railway, a city street cleaning shop, workings of the Universal Waste Products Company, a coal yard, and manufacturing establishments running south from the footings (still visible) of the Callowhill St. Bridge. Closer to the present I-676 bridge and east of the Reading Railroad tracks, Philadelphia dumped its coal ash, manure, kitchen waste, and glass bottles, among other refuse. Whether it is from the street cleaning shop, the waste products company, or the municipal dump, portions of the city’s detritus are strewn along this hillside. The aggressive tree removal in this vicinity has made these bluffs accessible revealing the remains of Philadelphia’s street life.

As sanitation historian Martin Melosi has pointed out, most practitioners of the early field of urban sanitation thought of the issue of waste disposal in terms of pure engineering. Armed with their expert knowledge of disease propagation and the technical systems of waste removal, municipal engineers enthusiastically urged “efficient” removal of generalized “filth” from city streets. While popular notions of street use were changing and streets were seen less as social spaces and more exclusively for travel, Philadelphia in 1890 had over 1,151 miles of streets and alleyways. By contrast, though it only comprised the borough of Manhattan, New York possessed 575 miles. But despite the need to efficiently clean its streets, Philadelphia, always the friend to private initiative, was one of the last cities in the country to end its private contract system of street cleaning in 1921. In his remarks to the twenty-fifth annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, president of the city’s Board of Health, Dr. William H. Ford admitted that “the contract system became a disgrace to the city and reform movements were instituted, but with little success.” The only brake on the contract system was a yearly open bid process in November. As Melosi points out in his Garbage in the Cities, the short amount of time between November and the new year meant that the review clearly favored the knowledgeable incumbent contractor. Philadelphia, however, soon embraced the street cleaning craze and uniformed members of the city’s Bureau of Highways and Street Cleaning Department [nicknamed White Wings] would parade to popularize clean streets.

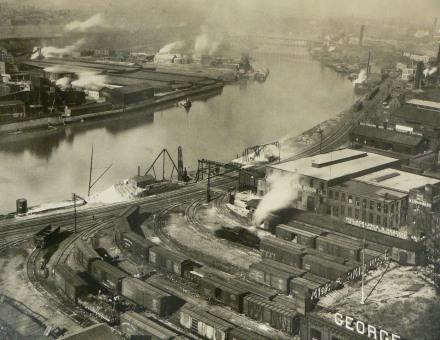

To sanitarians, the need keep streets free of coal ash, vegetable matter, and compacted excrement coupled with the practical realization that the Schuylkill bisected the city meant that large scows of waste continually plied the river. After docking at a municipal dump just north of Vine St., a large clam shovel probably offloaded their contents into rail cars which were traveled over the Reading tracks into the wedge of land hemmed in by 24th St. west of Park Towne Place, now occupied by a portion of the Von Colln ballfields. The 1942 City Planning Commission maps show a “city dump” north of Vine St. and a 1958 Sanborn map shows the presence of a “dump wharf” on the river.

With an abundance of trash, coal ash, and other waste nearby, the Universal Waste Products Company probably benefited from low transportation costs. Though it is unknown what exactly the company produced, the late 19th century saw great strides in waste reclamation. The USDA experimented with turning street sweepings into fertilizer. Some companies substituted half-burned coal “clinker” for gravel in concrete. Others processes removed ink from newspaper for reuse. “Coalesine” was a biomass fuel precursor made from compacted refuse [Melosi, Garbage in the Cities, 165].

The destruction of the waste district in the late 1920s, which occurred alongside the construction of the Art Museum represented the waning importance of the engineer/sanitarians and the rise in stature of an aesthetician/City Beautiful class. Both groups had worked towards civic improvement, though the latter thought the necessary piles of ash and trash an aesthetic horror. By the 1920s, though the intensity of the City Beautiful movement had waned, cities were increasingly reconnecting with their rivers as suggested in John Frederick Lewis’ 1924 polemic Redemption of the Lower Schuylkill or The River as It Was, The River as It Is, The River as It Should Be. A 1921 photograph of the district in David Brownlee’s Building the City Beautiful pictorially reflects this tension between clean streets and clean vistas; nestled in the hollow below the rising steel frame of the Art Museum is the waste district: the last nonconforming noxious industrial quarter still left on the Parkway.

More pictures of the waste district in 2007 [here].

Omfg dat was a lot

that is alot but i only need to read the good stuff