an study of built environments / landforms / cultural geographies

When the Schuylkill river was a conduit for coal, lumber, refined petroleum products, stone, and other finished goods, nearly every crossing south of the mound dam at Fairmount was of sufficient height to allow barge traffic. Some like the University Ave Bridge, the South Street Bridge, the CSX rail bridge (that carries our vaunted trash trains to us), and a tiny one track ex-PRR railroad swing bridge south of the Grays Ferry Bridge had mechanical appurtenances enabling them to open, swing, and elevate around river traffic.

The PRR swing bridge locked in the open position and the currently-used railroad bridge just south have the distinction of being the only two swing bridges in the city of Philadelphia. During the heyday of civil engineering, swing bridges were some of the most innovative — and trickiest — bridges to execute. Unlike a drawbridge or a bascule bridge, swing bridges were almost exclusively dependent on their central pivot point which is situated within the ship channel. Barges striking the central pier could damage either the central span or its pivot or bring the entire structure out of true with its approaches. The central pivot also had to be maintained, cleaned, and lubricated. New York City’s Third Avenue Swing Bridge, the only in that city, still requires consistent upkeep.

Continue reading “You Turn Me Right Round: Open PRR Swing Bridge, Grays Ferry”

In terms the story of its past use, the Schuylkill River is still a hidden river. And while we know more and more about our emerging built environment we know less and less about the historical/cultural forces [attitudes toward land, attitudes toward users of built space, attitudes toward public and private rights] that wrought so much havoc on this section of our urban environment.

The Fairmount Park Historic Preservation Trust is currently removing nearly a century of overgrown vegetation on the south side of Lemon Hill with the intent of making visible from Kelly Drive Henry Pratt’s Georgian mansion: around which were planted the citrus fruits that gave the hill its name.

Officially, the project is termed a “viewshed” restoration; it’s an attempt to restore the look of the hill to roughly its state in the mid to late 19th century and also to allow those on the hill a clear view of the Schuylkill. Usually, preservationists working with landscape crews use historic images to pinpoint overgrown areas and remove shrubs, small trees, and undergrowth around important cultural features. In the Lemon Hill project, two factors prevent preservationist from restoring the hill’s landscaping to before roughly 1870. Images of the hill prior to 1870 tend to be woodcuts, lithographs, oil paintings, and watercolors of various quality. Most are extremely stylized and amateurish with perspective and scale fluctuating wildly. These are helpful in a general sense and give an impression of clearings on the hill. After 1875, thanks to commercial photographer James Cremer, the photographic record of nearly all of Fairmount Park substantially improves. His stereoscopes of the park’s statuary, landscaping, and structures were sold widely and are an indispensible tool in recreating historic landscapes.

Perhaps unfairly, Fairmount Park has always suffered in comparison to Central Park, Prospect Park or any other Olmsted project of note. Recently in the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Historian Michael Lewis has tried to champion the “sophisticated” designs and designers of the Park prior to 1867 — the date Lewis contends others begin their analyses. Lewis appears overly preoccupied with defending Sidney’s 1859 plan for Fairmount against a straw man Olmsted and his estimation of Sidney’s non-moralistic pragmatic design is mired in taste. In reality, James Clark Sidney (and his partner Adams who, apparently had little to do with the design) were devoted to the image of fussy overcurvaceous parks found throughout A.J. Downing’s unintelligible villa design books. They had not clearly separated the park from the city, they merely cast “serpentine” paths among the topography, and many of the park’s principal roads seem carriageways and not pedestrian paths. (Hence, today Lemon Hill to Sedgely down to the Girard Avenue Bridge is the domain of cars and wide open spaces.) Sidney, a cartographer, was an imitator interested more in the “tactile and useful…than the moral” according to Lewis and did not conceive of moving through a sequence of structured spaces as a kind of pacifying program. But while Sidney lacked both creative techical vision and a well-developed philosophy of landscape architecture, the flaws of Lemon Hill are not solely rooted in design. The Park Commission’s notorious financial deterioriation in the 20th c. has allowed overgrowth to swallow up the few interesting features of Sidney’s plan.

Take for instance, the great stone staircase at the very foot of Lemon Hill (very top). If cleared of growth and opened, this staircase and the network of paths behind it will induce park users to cross Kelly Drive thus linking the vital Lloyd Hall-Waterworks-Boathouse Row complex to Lemon Hill. These are original to Sidney’s plan. Consider, too, that Sidney’s carriageways on Lemon Hill were praised by Gardener’s Monthly (1859) for “affording the most exquisite views up and down the river.” Aside from Fall and Winter, the Schuylkill is completely occluded by the dense stands of trees that have flourished since 1859. To allow views down the viewshed, the Trust and Commission will remove trees as they did near the future skate park along the river path. Sidney’s design for the original Fairmount Park is clearly not in the same league as Olmsted’s flagship parks. Perhaps the most attractive feature of the Fairmount Park System is not its classically well-landscaped rustic sections but its watershed parks (which themselves are manufactured). However, efforts like this viewshed restoration (which I urge you to follow) will undoubtedly reveal the hidden nuances of Sidney’s plan.

Dennis Clark’s research into the districts once known as Ramcat and Schuylkill piqued my interest in trying to reconstruct the environment of mid-19th c. Philly. In attempting to figure out if the areas on the east bank of the Schuylkill River between Vine and South were populated by wharfs and coalyards — as he described — I tried to plot all the “coal dealers” I could that were listed in the business section of McElroy’s Philadelphia City Directory of 1861. At first I equated “coal dealer” with “yard” but I don’t know enough about this industry to suggest that every “dealer” kept a stockpile of coal on his property. If anyone knows I’d appreciate confirmation. Here’s a link from www.philageohistory.org to the page of McElroy’s I used.

Here is the plotting of the coal dealers using Windows Local Live.

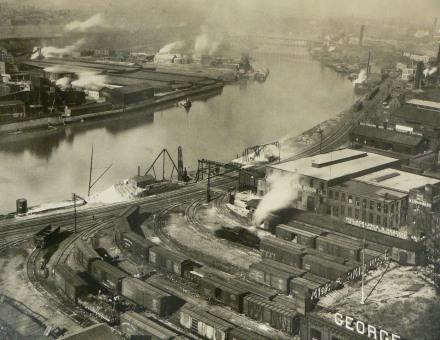

In plotting 70 coal dealers (just through H) several interesting features of this industry and an industrializing Philadelphia emerge. I anticipated that dealers would be located on the eastern bank of the Schuylkill River, and along the Delaware. I also figured that as a major commercial thoroughfare, Broad Street between Vine and South would have its share of coal dealers. I did not expect such a high concentration along Walnut St. between 4th and Front Sts. As the below may shows, one of the city’s major “public landings”, (which probably looked like the Race St. wharf), was located there. These coal dealers probably profited from being in close proximity to other dealers for information-sharing purposes. News about shipments, new markets, and fluctuating prices would easily pass through these coal dealer communities.

The distribution of these dealers also shows the limits of 1861 Philadelphia. As this 1840 map shows, mid-century Philadelphia was organized in a crescent around the Delaware, with development extending north into Northern Liberties and south into Southwark and Moyamensing districts. Roughly this crescent is replicated on my coal dealer map. Washington Ave., with its proximity to the Southwark RR, is fast becoming an industrial corridor.

Philadelphia’s Schuylkill River Park complex, an eight-mile manicured recreation trail paralleling an active freight railroad along the east bank of the Schuylkill River is an excellent specimen of post-industrial interstitial planning.

It also represents a dramatic break with Olmstedean park planning—though the park still reflects unnatural naturality with its clusters of antediluvian boulders and dramatically reconfigured riverbank lawns. But the main theme of the park is not to transport users out of an urban world but to foster reflection on the infrastructure of the city itself. In this way does the park resemble what the Germans call a landschaftspark such as that at Duisburg Nord in Bavaria: a multi-use playground for vigorous activity built on a former brownfield site.

In another way these parks tend to make the process of recreation a meditation on the structures and processes of the industrial world. Allowing views of the city’s concealed infrastructure and filled with objects of unknown function, these parks urge us to look critically at the urban/industrial mechanisms that once dominated our landscapes.

Just watching people use the Schuylkill River Path, it appears that the design of the park forces a sort of questioning mode. Whether it is a biker photographing a railroad signal or a woman reclining on a boulder lulled by the white noise of the Expressway across the river, the path designers have carefully created observation zones and structured the experience of moving through a world of transportation and movement.

Traveling northward along the path from its southern terminus at Locust Street, one is immediately struck with the numerous conduits of movement: from the trackage to the left to the vertical movement of pedestrians on the stairway astride the rather nondescript Walnut Street Bridge, to the traffic in the open subterranean tunnel across the river, to the commuter trains inching slowly across Paul Cret’s ominous black railroad bridge: one immediately understands the significance of travel along and across the river. As an expanding city whose core was nearly surrounded by water, Philadelphia recognized early the importance of bridges. By the latter half of the 18th century Philadelphia relied almost entirely on the western rural areas of Kingsessing and Blockley Townships for fuel and food. Philadelphia business elites also feared the loss of the city’s status as a grain entrepot to upstart cities such as Lancaster and Baltimore. The Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture avidly supported the construction of a fixed bridge that would channel western goods into city mouths and markets.

A bridge has straddled the Schuylkill at Market Street since the erection of the 1805 “Permanent Bridge,” a wooden structure operated for profit and appreciated for its design innovativeness. Mimicking highway onramps, today two inclined planes currently link the River Park path with the street grade of the Market Street Bridge. Ascending the plane to street grade, your eye is directed to two great symbols of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Thirtieth Street Station and four stone eagles salvaged from New York’s Penn Station which sit on the parapet of the Market Street Bridge.

Perhaps no other single company has altered the Schuylkill landscape north of Market Street more than the Pennsylvania Railroad. After passing under the Market Street Bridge, three elements testify to the impact of the Railroad on Philadelphia’s form. Just to the right of the railroad tracks after emerging from the Market Street Bridge, a curious black masonry wall appears. This is the last vestige of the infamous “Chinese Wall”: a blockwide elevated viaduct torn down in 1953 which led into Center City and the long-departed Broad Street Station. Both 30th Street and the railroad bridge were an effort to reduce the Railroad’s footprint in Center City in the late 1920s and early 1930s. In place of crenellated Broad Street Station and the obnoxious Chinese Wall, the Railroad constructed its modernist triad: 30th Street, Suburban Station, and a subterranean tunnel connecting them. With the demolition of the Wall in 1953-4, the Railroad opened up a development corridor between JFK Boulevard and Market Street. Other railroads vied for the highly efficient rights-of-way along the Schuylkill. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad’s main passenger terminal in Philadelphia, a turreted structure designed by Frank Furness, awkwardly stood at 24th and Chestnut Streets.

Meandering further north towards the Art Museum, 30th Street Station looms ever larger while bridge details snap into stark focus. Benches urge an inspection of stonework; of structural members; and materials. The airy and angular Cira Center appears as an apt conclusion to the tour through Philadelphia’s history of connectivity. As Inga Saffron has mentioned, the form of the Cira Center suggests travel of an intergalactic type.

With an extension of the trail to Fort Mifflin slated for 2012, the Schuylkill River Park and path offers new opportunities for meditations on the built environment. Snaking past electrical generating stations, oil refineries, and port facilities, the path represents not just a reclamation of lost industrial space but an opportunity to structure in space a narrative of Philadelphia’s industrial/material past.