[GOOGLE EARTH/HOG ISLAND SHIPYARD OVERLAY SHOWING SHIPWAYS]

My essay on the machine island of Hog Island is available on Phillyhistory.org. In that forum I present a nuts-and-bolts overview of the establishment of the facility, if a little indebted to James J. Martin’s revisionist essay on the mismanagement of the site. Martin’s essay, “The Saga of Hog Island, 1917-1920: The Story of the First Great War Boondoggle” is methodical and strident though slightly limited in its treatment of the social/labor dimensions of the site. Martin’s direct point is that the site was an utter failure, producing no meaningful warships to carry the fight to Europe during the conflict. But the larger design of his piece is to demythologize our patriotic appreciation of a disinterested private sector laying down its essential business to help the country in time of war.

[HOG ISLAND CRANES AT SHIPWAYS, 1918 OR LATER]

While Martin’s essay may inspire outrage, it also deepens our concept of military-industrial collusion in time of war: especially within the context of Philadelphia’s military industrial geography. In some ways war has always been good to Philadelphia as a concentration point of goods, raw materiel, capital, technical knowledge. We know of our own Robert Morris’ advantageous marshaling of Revolutionary war contracts and his shepherding of the Wharton and Humphreys shipyard, during the Civil War we know of the countless textile operators who leveraged Union League connections to gain lucrative contracts to make uniforms, drums, flags, and other accouterments of war.

[INFILLING OVER TIME — CHARLES ELLET’S 1843/PHILA. LAND USE MAP 1942/CURRENT GOOGLE EARTH OVERLAY]

Hog Island fits snugly within this story of an extraordinarily assertive and politically-connected manufacturing community striving to remain relevant during fat wartime periods. With corporations like the American International Shipbuilding Corporation holding out the Shangri la of full employment, most of these moves were couched in a populism that argued what was good for the city in wartime would be good for the city in peacetime as well. In this way, plucking the wartime plum may very well be a Philadelphia story—Hog Island being the most egregious example.

But between the traditional narrative of Hog Island as a patriotic foray into American industrial giantism and, on the other hand, the revisionist accounts which doubt the motivations that created the shipyard, there is the lost story of the men and women who made a barren strip of what 18th century mapmakers called “drowned land” actually work. In the absence of a good documentary record telling the story of the ethnic, racial, and gender groups that worked the shipways from 1917-1921 getting to know this story requires an almost phenomenological/empiricist approach: a “returning to the things in themselves.”

[1920S AERIAL PHOTO FROM U.S. ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS PORT REPORT]

In this context, the things in themselves have two chief ways of appearing—through the photographic record and the extant remains of that meaningful work and the environmental transformation that went on there. What we have left of Hog Island, which most say is minimal, constitutes an unexplored reality anterior to that reality we have constructed in historical discourse. Because Hog Island shipyard was a scratch-built place, a kind of rapid transposition of a functional urban industrial landscape onto an unforgiving void, its evanescence may be the signature of its Americanness. But its overwhelming absence, the paucity of its remains frustrates any attempt to define Hog Island as having any particular identity. It may be argued that the sheer abundance of American industrial ruins exhibiting no real “place” is their undeniably American quality.

[RUINS OF SHIPWAYS, HOG ISLAND]

Key to providing Hog Island with a sense of identity is an approach which prioritizes seeing and qualitative experience. In the midst of the present Hog Island—still a veritable machine island of airport runways, tank terminals, and access roads—are the remains which show that through tireless human intervention, the site articulated its special relationship to the Delaware, to American history and to the industrial history of Philadelphia. This is more so real now when you can still see the pilings sunk into the banks to form long inclined planes. These are the same pilings which “a crew of 11 negroes … put down 220” of in 9 hours and 5 minutes, setting a new world record.

So while Hog Island is conceived of as a supremely engineered place, a kind of geometrized antihuman complex built to satisfy the logic of capital and industrial war, the process of visualizing its construction and exploring its ruins tempers this assessment. When one looks at the photographs of the shipyard’s construction in the Philadelphia Record collection at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania or visits the site, you get the impression that Hog Island had a very human, almost personal origin.

[PILINGS FOR SHIPWAYS]

The paradox of an industrial complex, most of which is gone, having a decidedly human component has to do with the images of its construction. Though I didn’t address this in the Phillyhistory.org piece, by most accounts it appears that the American International Shipbuilding Corporation had a clear hierarchy of priorities when deploying heavy earthmoving equipment. Whether this is due to a shortage of machinery is unclear but you rarely see heavy equipment being used for anything but the construction of the shipways or the wet basin, which were the heart of the operation. There are no mechanical devices used in the construction of the infrastructure necessary for human habitation—the sewer and water lines, the barracks and canteens. There’s even a strange shortage of heavy equipment at work in constructing the shipways.

[SHIPWAY DECKING, NOTE INCLINE]

What strikes one as they look through these photos, most of which were taken during the fall and winter of 1917-1918 is how human intensive the labor was. Ditches were dug by hand and men waded into the river to pour foundations or excavate the shipways. While there is a oneness with the earth conveyed in these photos they also suggest something rough hewn , disorganized, and almost comical about the construction. There are enormous stacks of wood and buildings supplies everywhere on the site. Wood was the prime material for building outbuildings, for bulkheads, pilings for the intricate shipways, and for the floors of the shipways themselves (some of which are left). The piles of wood strewn about the yard do give the impression of wastefulness but material management in the early months was a vexing problem. Aside from the skyrocketing cost of construction, much of the early criticism of the yard’s management stemmed from the logistical nightmare of managing both yard and ship construction simultaneously. Clearly, the remoteness of the site, poor transportation, lack of coordination between suppliers, minimal cost oversight, and the external pressures to meet contracts all flustered government inspectors and construction engineers accustomed to the rote efficiencies of good shop management.

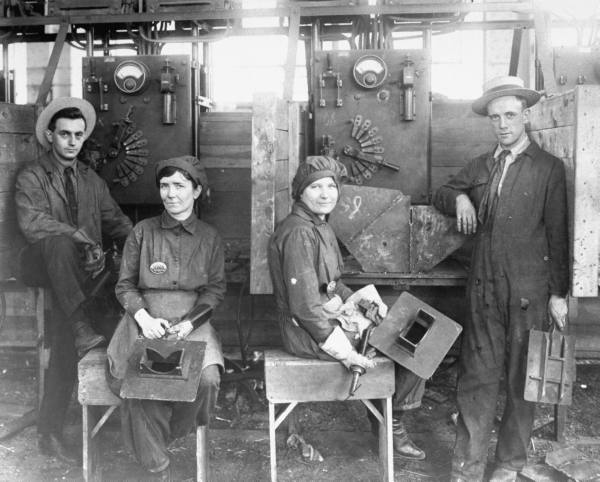

[FIRST WOMEN WORKERS AT HOG ISLAND, ELECTRICAL DEPARTMENT]

[INDIANS FROM CARLISLE SCHOOL AT HOG ISLAND]

True to the lavish descriptions of the site’s voracious appetite for people and things, Hog Island drew great tides of war materiel and human labor its industrial maw. Because of its size and its importance, Hog Island, perhaps more so that any other wartime industrial operation in Philadelphia was a democratic crucible. During its brief time in existence, Hog Island was the largest industrial employer in the region, dwarfing the second largest Baldwin Locomotive Works by several thousand. Because of its military import, Hog Island rarely turned anyone away. Everyone from world class sculptors, to Indians from the Carlisle School, and later women worked in the yard. But despite it being a military facility there was great fluidity in the workforce. During the tough winter of 1917-1918, the American International Shipbuilding Corporation reported weekly turnover rates of 700 percent. On rainy days, the yard could see a decrease in workforce of thousands. And all of cantankerous Philadelphia was represented. Blacks served alongside ethnic whites, all working nine hour shifts and contributing in any small way possible to the better production of ships. But there is a great void as to how these groups worked or failed to work together. There is also a great gap in the story of labor unrest at Hog Island. These are the stories that lie concealed in the murk of history. But if these tales are half as resilient as the thousands of pilings that still hold fast against the Delaware, they’ll be found soon enough.

[MORE HOG ISLAND PHOTOS]

what is the relationship of the old girard point communityand the hog island shipyard if any??

My paternal grandfather worked at Hog Island-I actually have an engraved brass “paper weight” that was issued to him as a thank you for his service there. My question is: is there any list of the people who worked there or do any of the pics have names with them? I’d love to know what his position was there.

His name was Francis (Frank) Michael Carroll (his paper weight was engraved to FM Carroll who served his country during the Great War as a builder of the bridge of ships at Hog Island 1917-1920).

Did you ever receive an answer? I would like much the same info for my grandfather.

I have a complete album of the launching of the U.S.A.T. Cantigny at Hog Island in 1919 with the attendance of King Albert of Belgium as a sponsor of the ship and with Prince Leopold also in attendance. There are innumerable photos of the attendees as well as of the shipyard itself. The album yard photos were taken in 1918 along with photos of the arrival of the King in 1919 and with his christening of the ship at launching. An historical album of the Hog Island shipyard.

USAT = US Army Transport

does anyone ever get a meaniful information from these posts

Hi Christopher, question for you: In your research, did you ever find any definitive link between Hog Island and the hoggie sandwich? Or, is there any evidence that Hog Island workers were indeed called “Hoggies?” Thanks